“Git offa mah property you damn Yankee som beech!” commanded the little man with the tobacco-stained teeth. “And stay away from mah Niggah, you heah?”

Reuben’s first encounter with the residents of Linn County had rapidly gone south. He could tell the little man meant business because his hand had moved to the grip of a very big Colt Navy Revolver.

“Didn’t mean no harm, Sir. I’m fixin’ to find me a place hereabouts. This here colored man is makin’ you some pretty good furrows with that John Deere plow. I needed to watch.”

“You best be a-gittin along.” barked the little man. “Maybe head on back to Ioway.”

Reuben released the wagon brake, shook the reins, and hollered, “Giddy up!”

The conversation was over, but Reuben had learned a few things about his new surroundings. The Black man plowing the field knew more about busting Kansas sod than his master. They had had a productive conversation.

“You a free man?” Reuben had asked as the man brought his plow to a stop near Reuben’s wagon.

“Nah Suh, I belongs to Massah Morgan”

“Where did you come from?”

“The Morgans have a tobacky farm in Missourah. They sent me and Massah heah to stake out a clain for plantin’. Massah’s gonna help Kansas become slave.”

“How does that sit with you?”

“Tain’t nuthin I kin do bout it. I’s born a slave and I recon I’ll die a slave. You white folks can talk all youse want, but nuthin ever changes.”

“Got family?”

“Wife and three chillen back in Missourah. Massah say he’ll bring ‘em heah soon as we make good. I ain’t sure how long that’ll be cuz Massah tain’t much fer farmin.”

“What happens if you don’t make good?”

“Don’t wanna think bout that. Massah might sell muh wife ‘n chillen down the river. They’s worth more in N’Orleans than they is in Missourah.”

“Well I hope that don’t happen then. If I had my say, Kansas will be a free state.”

“Well Suh, I hopes youse right. What brings you way out here?”

“I’m gonna get a place, raise some good horses and cows, and marry the purdiest gal in Iowa. This land looks like it might work for both farmin’ and grazin’. What’s the market for beef and grain?”

“Massah takes care of the sellin’ and we ain’t growed much. Mostly corn and wheat. Massah don’t know nuthin’ bout cattle, so all we’s got is mules for plowin’.”

“Is this the right trail to Sugar Mound?”

The Black man nodded.

“How far?”

“Bout three hours with a rig like your’n. Jes look fer a big ol’ hill wid a passel of Sugar Maples. Cain’t miss it.”

Both men looked up as a rider approached.

“Here comes Massah, I better be gittin me back wid dem lines. He don’t cotton much to sluffin’ off.” He grabbed the reins and prodded the mules to resume his task. The steel plow lurched forward and ripped into the virgin sod.

Reuben’s thoughts wandered as he waited for Mister Morgan to approach. It was always good to talk with a fellow farmer, even if he happened to be a slaveholder. The Black man plowing the field had been helpful. His well-cared-for mules were harnessed to a John Deere plow, just like the one Reuben had in the wagon. Reuben noted that the man’s furrows in the virgin Kansas sod were perfectly aligned. Each new cut lifted the sod and deposited it on its side in the previous furrow. The man plowing the field was good at his craft. Lucky is the farmer who can find someone to plow like that, Reuben thought. And it didn’t matter if that man was Black or White.

He first noticed that the man was Black when he turned the rig around. His well-muscled ebony arms held the plow steady as he began his return. His black face gleamed with sweat underneath his course straw hat.

Reuben knew that few slaves had been brought to the Kansas territory. There were even fewer free men of color there. Kansas was no place for growing cotton and tobacco, the two labor-intensive crops that fueled the slave trade. Moreover, many midwestern farmers coming to Kansas didn’t appreciate competition from Black labor, free or not.

Reuben knew a little about slavery. He had grown up in Appanoose County, Iowa, just a stone’s throw from the slave state of Missouri. The “Little Dixie” part of Missouri where slave-holding was economically feasible was only about a hundred miles to the south. He’d seen slaves on his occasional trips into Missouri. The slaves he had seen worked hard, often singing to relieve the boredom. It was not lost on Reuben that slavery had its darker side. He knew about the cruelties inflicted upon them by hired overseers. He knew that families could be separated and sold off at the whim of their owners.

Years ago, he had seen runaway slaves seeking aid at the DeLay farmhouse. His father, Joseph, provided them with food, and directions. Sometimes the DeLays sheltered them in the barn. All that ended with the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Slave hunters now had free rein to pursue runaways into Iowa. Local people and law enforcement officers were required to aid them or at least stay out of their way. It was a federal crime to harbor or help a fugitive slave in any way. A few of his neighbors were eager to collect the rewards for recovering the escapees. For Fifteen Dollars they would condemn a human being to eternal bondage. The captured runaways were often held in the county jail until their owners came to claim them.

After the 1850 law went into effect, some brave Iowans decided to resist. They became conductors and station masters on the Underground Railroad. They would hide fugitives from the “men stealers” and arrange for them to escape to the North. Chicago was the preferred destination for the runaways. There, they could book passage on a steamer to Canada. Only in Canada could they be free from the fear of capture and return to slavery.

Rumor had it that Reuben’s Uncle Jacob was involved with the Underground Railroad. As he got older Reuben found that the rumor was true. Jacob was a Methodist preacher interested in more than just saving souls. His faith told him to save men from the cruelties of slavery. For Uncle Jacob, slavery was wrong; a sin against God. He was also a man of action who lived his faith. Being a circuit-riding preacher he had the perfect cover for his nocturnal trips to the next station on the line.

Reverand Jacob DeLay had built a hidden cellar under his house for his charges. It was a risky business. Sometimes the slave-hunters would persuade the Sheriff to help them search Jacob’s place. Somehow Jacob always knew about the Sheriff’s intentions and moved his human cargo to safer locations. Though Uncle Jacob had been careful not to involve Reuben in any illegal activity, he was occasionally asked to mount a fast horse to carry a message or warning to some remote station on the line. It was exciting work for an adventurous young man.

Reuben well-remembered his Uncle’s passionate sermons on the evils of slavery.

“Man is imperfect and greedy. He easily falls under the Devil’s sway. Then he begins to sin to satisfy his wicked desires. Abominations abound in the mind of a sinner. The greatest of these abominations is SLAVERY!

“Slavery is the most base and ignoble practice ever undertaken by man. It is based solely upon AVARICE! Such avarice hardens the heart and makes men callous to the feelings of humanity. Ought we not be ashamed for not speaking against this evil institution that makes men chattel?

“The commerce in human beings causes our God to weep. The barbaric treatment of the enslaved rests on the consciences of all men, not just slave-holders. What have we done to end this abominable practice? Not enough, I think.

“Would you consent to the enslavement of your brother, your sister, or your neighbor? Then why do you countenance this abomination in these United States? Do you support the ripping of families apart for the sole purpose of profit? What profit a man if he loses his soul? Have you seen the lash marks of the overseer and looked away? Have you bought the produce of enslaved hands because it was cheaper? Do you greet the oppressed stranger as you would your neighbor? Were you not once strangers in a strange land? When your God asks you what you did about the chains and scars of slavery, what will you say?”

Uncle Jacob’s sermons got mixed reactions from congregations. Some folks, upon realizing the subject was slavery got up and walked out. They had their reasons. It was common for Northerners to fear the competition from freed slaves in the labor market. Others worried that liberated Blacks might corrupt the blood of the White race. Some just felt that Blacks were lazy, stupid, and inferior. Most Iowans of the day, however, showed at least some sympathy toward the plight of the enslaved. Though Reuben wasn’t a fire-breathing abolitionist, he believed that slavery was inherently wrong. When Uncle Jacob took up a special offering at the end of an anti-slavery sermon, Reuben would dig into his pocket. He understood well that the money went to support the illegal activities of the Underground Railroad. His Uncle was flaunting a bad law to achieve what he felt was God’s will. Perhaps Reuben would have to make that same choice someday. His move to Kansas was making it harder to ignore the issue. Much harder.

Helping Reuben make his choice was the little man with the big gun. The man wore a broad-brimmed planter’s hat with a tan linen coat. His face had the paleness of one who spent most of his time in the shade. Reuben suspected that a look at his hands would reveal he hadn’t spent much time doing real work. Besides the big Colt revolver, Morgan had a coiled whip over his shoulder. Though Reuben always gave strangers the benefit of the doubt, Morgan’s countenance seemed foreboding.

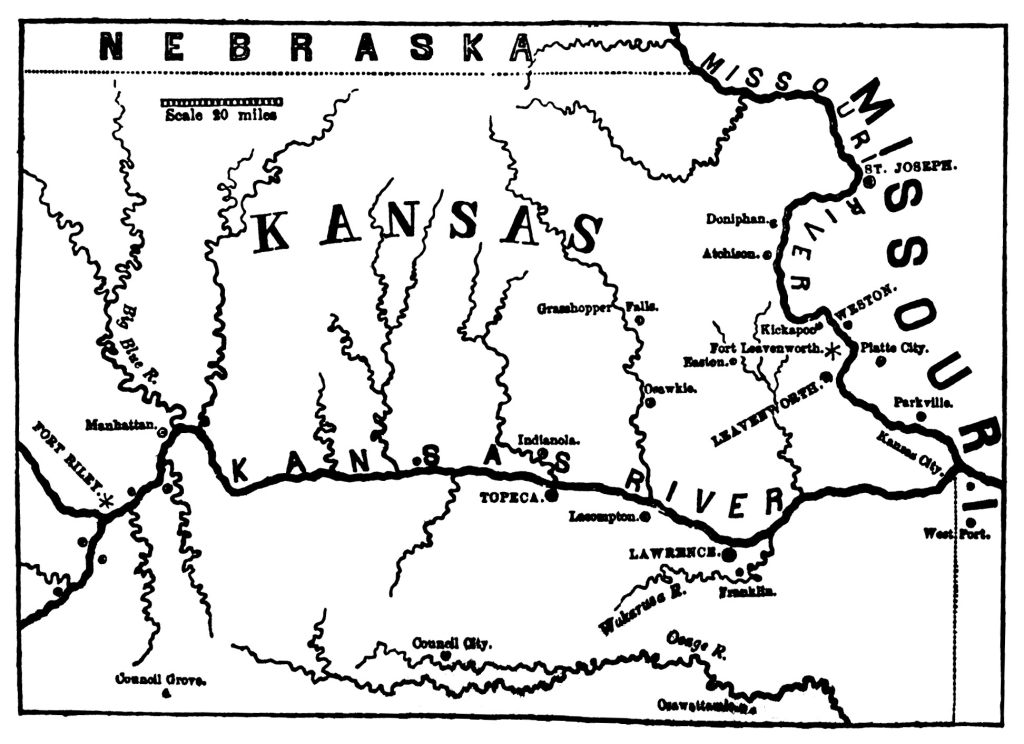

Could free and slave labor coexist in the same place he wondered? That was the issue the Kansas-Nebraska Act was supposed to solve. The decision on whether to become a free or slave state was up to the people who settled there. Senator Stephen Douglas, the bill’s author, called it “Popular Sovereignty.” Unfortunately, the bill had caused a race between settlers from the North and South to see who could fill up Kansas first. The majority would then decide the issue. This was already causing friction as Reuben drove his wagon into Kansas in the Spring of 1856. Early efforts to establish a constitution under which Kansas would become a state had caused considerable animosity. There were two competing constitutions, one free and one slave. In the case of the Lecompton Constitution, thousands of Missourians had been persuaded by free booze and transportation to spend a day voting as pro-slavery Kansans. The delegates sent to write the free-soil Topeka constitution were selected from the anti-slavery contingent. Neither side recognized the other and Congress was reluctant to approve statehood under either constitution.

Reuben sympathized with the free-soil faction but had not joined their cause. Men like Morgan were pushing him in that direction.

At first, Reuben and Morgan had discussed what crops grew well in this part of Kansas. The tone changed when he casually mentioned that the country looked like Iowa when his family settled there in the 1840s. As it turned out, Iowa was a land full of hostile abolitionists to slave-owning Southerners like the man he was speaking with.

Reuben should have known better. Ever since he crossed over into Kansas at Leavenworth, he found himself amongst dueling groups hell-bent on making sure Kansas would become either a free or a slave state. The Leavenworth crowd was decidedly pro-slavery. The territorial lawmen and the commander from the fort there were quick to intervene on behalf of the pro-slavery faction. Those with Free State sentiments were made to feel unwelcome, often by a nighttime raiding party. The Fugitive Slave Act was vigorously enforced. People who aided runaways faced prosecution.

It was a different proposition when he arrived in Lawrence. The area had been settled by rabid abolitionists from New England. They were there to do the Lord’s work of making Kansas free. Their tactics resembled those of the pro-slavery faction. If they couldn’t persuade those who didn’t share their opinions on slavery to leave, they burned them out. No wonder everyone in Kansas went about their business armed like they were going to war. Reuben had seen a man in Lecompton who had two pistols and a Bowie knife stashed in his red sash. He had a rifle slung over his shoulder and what looked like the hilt of a dagger sticking out of his boot. All he needed to complement his baggy costume was a Derringer in his front pocket. Reuben wondered if it was passed time to pull his old muzzle-loader from its protective blanket and oilskin cover. The locals were making him nervous.

Reuben still wanted to put the slavery issue to the back of his young mind. All he needed was a piece of land to call his own. There was a certain raven-haired beauty back in Iowa who seemed eager to share it with him. Like his father and grandfather had done, he intended to make a new life on the frontier. He wasn’t looking for trouble.

As the wagon jolted over the rough trail, he heard the sharp crack of a whip. Morgan was intimidating his slave with a near miss. Reuben felt a flush of anger.

HISTORICAL NOTES:

Reuben DeLay’s obituary says he first came to Kansas in 1856, settling in Linn County. Located on the Missouri-Kansas border, Linn County soon became a hotbed of activity in the contest to make Kansas either a free or slave state. This led to violence and intimidation on both sides of the border.

The fictionalized sermon by Jacob DeLay is based loosely on a 1774 sermon by Elhanan Winchester.

Chapter 3: Montgomery- https://azrockdodger.com/2025/01/21/chapter-2-montgomery/

Main Menu- http://www.azrockdodger.com

INDEX: Unbowed: The Saga of a Civil War Cavalryman- https://azrockdodger.com/2025/02/06/unbowed-the-saga-of-a-civil-war-cavalryman-index/