The Bike That Wouldn’t Die

little change

There have been many great motorcycles over the years. The Crocker, the Knucklehead Harley, the Triumph and BSA Twins and the Brough Superior were all ahead of their time. They introduced new technologies, went faster and looked better than their predecessors. They all faded into the dustbin of history as better machines took their place. All, except one.

the Royal Enfield Motorcycle Company adopted the slogan

“Made Like A Gun”

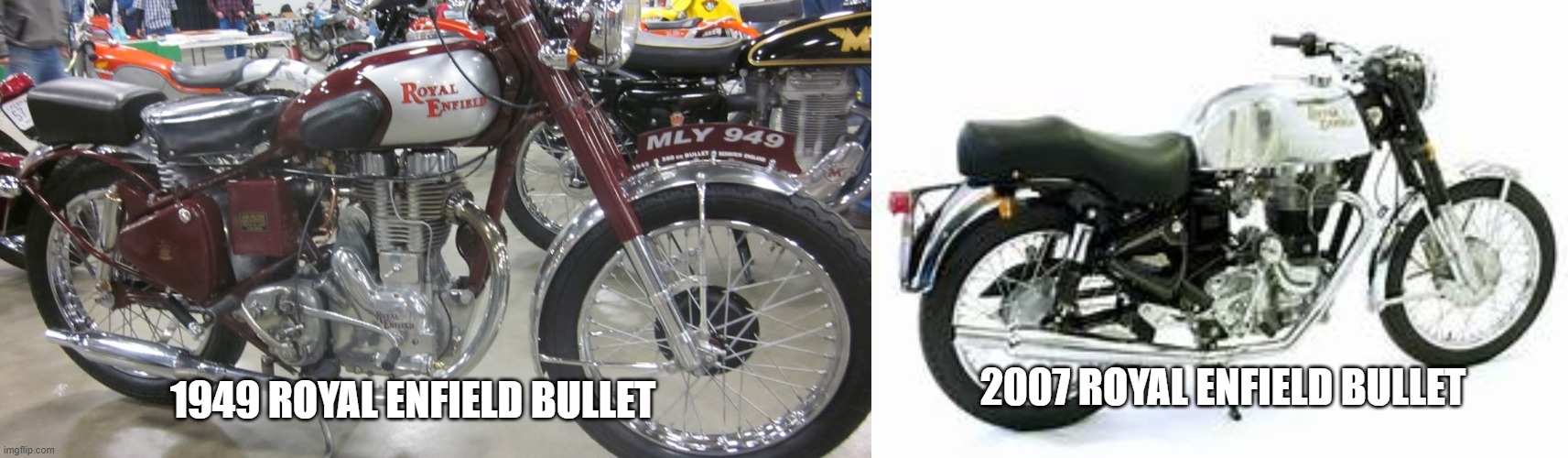

In 1949, the British Marque, Royal Enfield introduced a new version of its Bullet. It came with a brand-new overhead valve engine affixed to the frame with a recently developed set of telescopic front forks and a revolutionary swing arm rear suspension. Critics said it wouldn’t work. The rear end would be bouncing all over the place. Everyone knew that the only springs a motorcycle needed were on the rider’s seat. Besides, if you went off road you simply stood up and let your knees absorb the bumps.

in off-road competitions in the late ’40’s and ’50’s.

The critics were soon proven wrong. The new Bullet won two gold medals at the International Six Days Trial. (The ISDT is an endurance run for off-road motorcycles which remains one of the pre-eminent motorcycle competitions in the world.) The Bullet continued to perform well off-road throughout the 1950’s while sales of street versions were strong. By the ‘60’s, however, powerful, light-weight two stroke bikes began to dominate the off-road scene. The Bullet would soldier on as a street bike and military scout/courier machine. India started importing military versions of the Bullet in 1949. They were ideal for patrolling remote stretches of its borders. During the 1950’s, the famous American Indian Motorcycle Company imported Royal Enfields under its own brand name.

In its home country of England, the Bullet began to fade in popularity as more modern designs took its place. The invasion of cheap, reliable Japanese bikes in the 1960’s didn’t help. Royal Enfield of England stopped making the Bullet in 1967. Three years later, the whole company folded. That should have been the end of the Bullet story, but it wasn’t. Remember those military models exported to India?

as used by the Indian Army starting in 1949

Demand for the Bullet by the Indian Army remained strong after their initial 1949 order. In 1955, a factory in India started assembling Bullets from parts kits shipped from England. By the next year, India had the tooling to make its own Bullets for sale to the public. Demand was solid and Indian tariffs kept out the competitors that were killing British motorcycle sales. Sales to private owners soon outstripped the demand of the Army. About 20,000 bullets were built each year. With no competition, the design was frozen in time. Eventually, the machine became an anachronism, prized by people who couldn’t afford or lacked the skills to build a restored classic bike. By 1977, Enfield of India was exporting the bikes back to England. In the ‘90’s it was modified to meet US specifications and small numbers of them began to appear on our highways.

Very few changes were made to the endearing 1949 design over the years of production in India. A Rube-Goldberg linkage was developed to switch the gearshift to the left side on American models. The antiquated drum brakes got bigger. An alternator replaced the gear-driven generator providing brighter lights. Crude smog equipment was added. In the 2000’s Bullets got a much better five-speed gearbox without the sloppy linkage of the old Albion four-speed. Later models even had electric start, but a redundant kick-starter remained for purists. (Bullets were renowned for their ability to start on the first kick.) The final 500cc Bullets with the original frame and engine style rolled off the assembly line in 2007. They were not much different from the first Bullets of fifty-eight years before. Though the new Royal Enfield 650cc twin has won the hearts of many old school enthusiasts, the Bullet remains a timeless classic.

is drawing lots of attention for its classic styling

I once owned a 2004 Royal Enfield Bullet “65”. It was an amazingly simple machine. With its tiny Mikarb (Mikuni knockoff) carburetor, it got 60 MPG. In spite of the antiquated design, it was fun to ride. I did find it too slow to use on 65 MPH highways. The big single had a visible thump as it idled at an incredibly low RPM. At higher speeds, the bike vibrated much more than a modern single.

The drum brakes were marginal. Mine had the newer five-speed transmission, but the rear brake pivot still crossed underneath the engine giving it a sloppy feel. Making matters worse, the pedal was a very flexible, stamped steel design. The front brakes weren’t much better. I planned my stops carefully and never followed too close. Welding was crude and the metallurgy of the alloy cylinder head was weak. A cast rocker arm broke once, leaving me stranded. I had to helicoil several rocker block stud threads when they stripped out of the soft alloy head. Adding to my woes, was a bewildering mixture of metric and Whitworth (British) bolts. I often replaced the latter with US thread bolts and aircraft locknuts. Removing the head was problematic because the head-bolt washers were so soft they riveted themselves to the studs. A weld on the fuel tank broke. Engine vibration required constant tightening of bolts and the front fender stays broke from the stress. The drive chain was an incredibly stretchy Diamond brand. I replaced it with a better chain at a thousand miles. Tires were high-quality Avons, but in a smaller size than I would have preferred. Tire options were limited due to the 19-inch wheel size.

Though I loved the Enfield, my 400cc dirt bike with stock gearing was at least 15 MPH faster and a lot more reliable. Eventually, I parted ways with the Bullet and got an f650 BMW for street riding. Then the retro-styled Royal Enfield 650 Twin came out. It is said to be a solid design. It will do the “Ton” (100 MPH). Too late for me…

LDT 3 Jun ‘21

Cycle World Magazine loves the 2021 Royal Enfield 650 Twin 2021 Royal Enfield INT650 | Cycle World