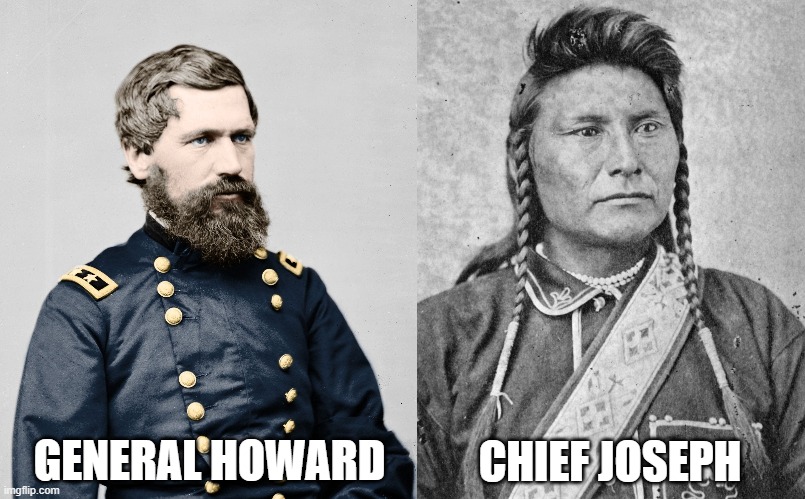

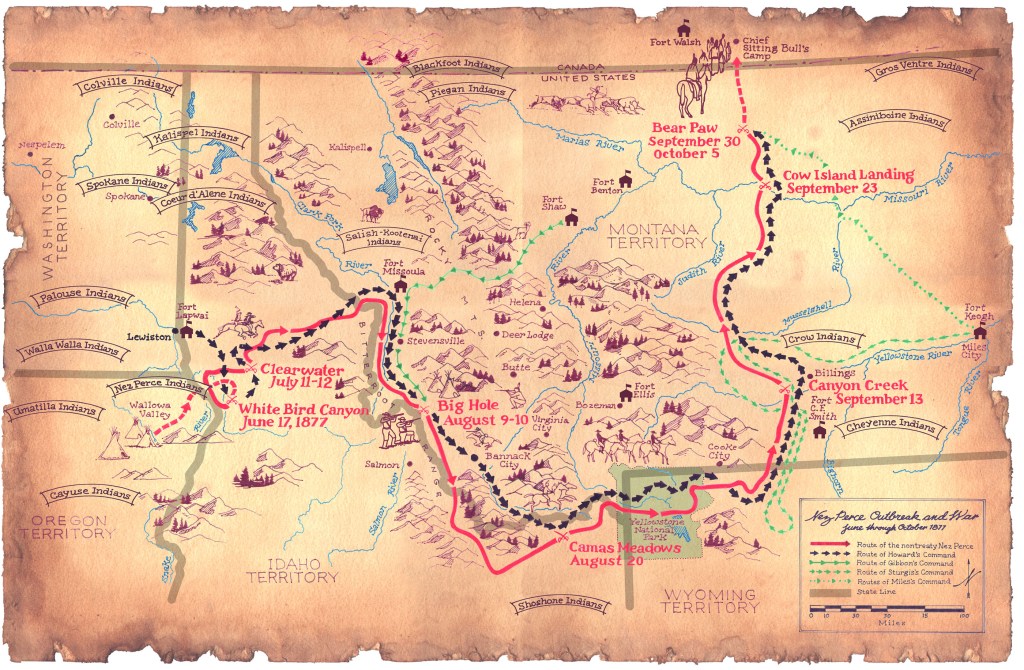

The pursuit of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce by General Oliver O. Howard in 1877 ranks as one of the longest running battles in the history of the American West. Howard chased Joseph for nearly 1200 miles across Oregon, Idaho, Wyoming and Montana. For the entire campaign, Howard was out-generaled by his wily opponent. It would be up to Colonel Nelson Miles to stop the Nez Perce in the Battle of the Bear’s Paw.

The Nez Perce call themselves the Niimiipuu (the people). Some forgotten French Trapper apparently mistook another tribe’s sign for them to mean that their noses were pierced. The tribe lived in the Upper Columbia River country of Northern Idaho and Eastern Oregon and Washington. It was the Nez Perce who welcomed Lewis and Clarck’s famished Corps of Discovery after their arduous 1805 trek over the Rockies. Occupying a land crucial to the fur trade and overland travel to the Oregon Territory, they quickly made friends with the new arrivals from the American and British fur companies.

Later they watched settlers and miners making their way into the Northwest. Missionaries brought them a taste of Christianity. One Nez Perce even translated the Gospel of Saint John into his own language. Many had put aside their buckskins and adopted the dress of their white neighbors, supplemented by gayly-colored bandanas. Preferring hunting and fishing over agriculture, they became fond of the latest in firearms. Superior marksmanship was one of their most notable skills. Each summer, they made annual journeys across the Rockies to hunt the buffalo of the Great Plains.

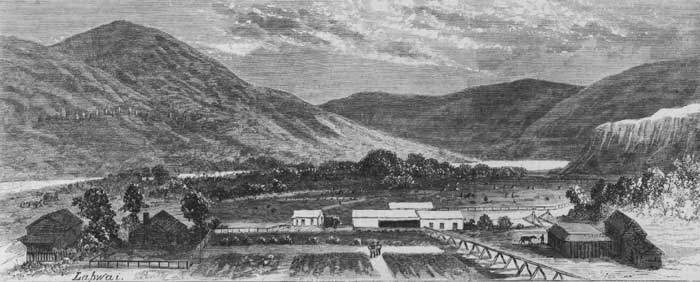

By 1877, there were two basic divisions within the Nez Perce. The “Treaty” group occupied the Lapwai Reservation in Northern Idaho. The “Non-Treaty” group consisted of various bands under chiefs like White Bird and Joseph who roamed free in other parts of the territory. Friction between the non-treaty Nez Perce and the Whites began to develop as more settlers and miners moved into their hunting grounds. In far off Washington, D.C. it was decided that the non-treaty bands would have to come in to the Lapwai reservation. The new Commander of the District of the Columbia (River), General Oliver Otis Howard, was tasked to bring them in.[1]

General Howard had experience both fighting and making peace with Native American tribes. As a young officer, he had seen service in the Seminole Wars of the 1850’s. More importantly, in 1872 he had served as a Peace Commissioner in Arizona and New Mexico. That mission had been wildly successful, bringing peace to an area long ravaged by wars with the Apaches. In between he had fought on the Union side during the Civil War, losing an arm in battle. At the end of the war, he was chosen by Lincoln himself to head up the Freedmen’s Bureau. In this position, he accomplished a great deal in assimilating the newly freed slaves into American society. Sadly, his role as peacemaker to the Nez Perce would not be so successful.

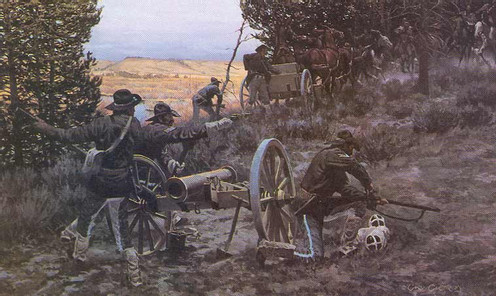

In early May of 1877, Howard called a council of the non-treaty Nez Perce at Lapwai to discuss the move to the reservation. Not wanting to appear weak, Howard negotiated with a heavy hand. The Nez Perce who refused to re-locate to the reservation would face war. To drive home the point, he arranged a demonstration of his powerful Gatling Gun. The Nez Perce took note. They resolved never to let themselves get anywhere near the cumbersome, carriage-mounted weapon. This knowledge would serve them well in the coming conflict.

Howard soon noted that the band most opposed to the reservation offer was a group he called the “Dreamers”. The Dreamers, or “Tooats” as the Nez Perce called them, were under the influence of a mystic named Toohoolhoolzote, or Too-hul-hul-sote as Howard spelled it. He preached that the Nez Perce should live freely, without cultivating the land or congregating on reservations. Disgusted by the prospect of being forced onto a reservation, Toohoolhoolzote told Howard, “We will go where we please, and do as we please. Who gave Washington rule over me?”[2]

A disgusted Howard threw Toohoolhoolzote in the stockade before the other Nez Perce could react. After they calmed down, hhen he took the chiefs on a tour of the Lapwai Reservation to pick out the lands that they would live upon. All seemed well with Joseph, his brother Ollokot and the other influential chief, White Bird. Upon returning to the Headquarters, Howard thought he had a deal. The non-treaty Nez Perce would collect their people and return to Lapwai in a month. He let himself be persuaded to release Toohoolhoolzote. Howard had achieved his “fait accompli”.

After briefly revisiting his headquarters in Portland, Howard returned to Lapwai via Fort Walla Walla to oversee the peaceful settlement of the Nez Perce on the reservation. His visit to Walla Walla was intended to calm the nerves of the local tribes and ensure they would not join any recalcitrant Nez Perce who refused to come in.

Meanwhile, the Nez Perce bands were assembling near Mount Idaho for one last Pow Wow before coming into the reservation. Warriors bragged about past feats of daring. Some nursed old grudges. A few got drunk. Soon a settler was killed, then four more. The panicked residents dispatched a courier to Lapwai begging for help. The just arrived Howard sent two companies of soldiers under Brevet Colonel Perry to their aid.

On June 16, 1877, Howard telegraphed his superiors, “The Indians began by murdering a white man. They have begun war upon the people near Mount Idaho, and Captain Perry started with two companies for them. Other troops are being brought forward as fast as possible. Give me the authority for 25 Indian scouts. I think we shall make short work of it.”[3]

On June 17, all hell broke lose for Perry’s force at the Battle of White Bird Canyon. They rode into an ambush in the canyon’s narrow confines. Thirty-four calvary men were killed. Others broke and ran losing most of their weapons and ammunition to the attackers.

.jpg/1200px-thumbnail.jpg)

A scout named F. Williams gave an unfavorable account of Col. Perry’s troops during the White Bird Canyon debacle. “….upon the first fire….the soldiers broke ranks and retreated.” Their officers couldn’t rally them as they fled 10 miles back toward Mount Idaho. Williams said that the Indians had “better guns than the troops and their aim was deadly.”[4]

Howard was left with only a small garrison of troops at Lapwai. He immediately telegraphed for more. They would come from as far away as Alaska and California. They would come by rail, sea, riverboat and overland marches. Eventually he would command even more troops dispatched from the Department of the Platte. These included soldiers from Fort Shaw, Fort Ellis and the new Tongue River Cantonment in Montana.

By June 22, Howard departed Lapwai with a force of 200 troopers and joined Perry’s decimated command at Grangeville, Idaho. Volunteers and troops from throughout the area soon arrived to bolster the ranks. From 3-5 July a small blocking force under Captain Whipple and Colonel Perry failed to stop the Nez Perce in a series of skirmishes at Cottonwood, Idaho. Over a dozen men were killed and a group of 17 volunteers were cut off and imperiled.

Howard’s main force finally caught up with the hostiles at the Clearwater River on July 11th. Howard’s gatling gun and Howitzers proved ineffective as the warriors kept their distance. That night Joseph and the Nez Perce were able to trap Howard’s force in a narrow bend with their backs to the river.

The next morning, July the 12th, the Nez Perce vanished across the river. Howard was slow to pursue them. They got away with most of their stock and camp equipage.

After the Cottonwood and Clearwater battles, Howard began to receive criticism from the press. He “has been severely censured by the press as an incompetent commander and he has certainly done nothing so far to leave any other impression,” reported the paper at Deer Lodge. The hapless Colonel Perry also came under fire for his failure to quickly rescue 17 volunteers who were separately besieged at Cottonwood on July 5th. Perry could see their plight, but could only comment, “There is no use; they are gone.” Getting no help from Perry, their commander, Captain Randall, ordered a charge through the Nez Perce lines. They reached a safer place but one of the men was killed and Randall was mortally wounded. An hour later, Perry finally ordered 50 men to their assistance. Meanwhile the Nez Perce simply passed by Perry’s defenses.[5]

A few days after the Clearwater battle, the Nez Perce hood-winked Howard with a surrender proposal. This delayed his pursuit, but only resulted in the surrender of a handful of tribesmen. The Nez Perce would use this time to flee towards Montana.

On Jul 17th, Generals Howard and McDowell began warning the citizens of Montana about the eastward flight of the Nez Perce.

“A majority of the hostile Indians have fled to the Lo Lo Fork trail eastward to the buffalo country.” Telegraphed Howard.

Curiously, McDowell added from his California headquarters, “I consider this a most important success. Joseph is in full flight….” Montanans were not convinced that a party of well-armed Nez Perce warriors coming at them was anything like a success.

Howard left Kamia, Idaho on the 26th of July for the long and tedious march over the Lolo Trail to Montana. The first day his command made a whopping 6 miles. They were now 150 miles behind Joseph. Howard hoped a detachment of Colonel Gibbon‘s troops at Missoula would hold the hostiles at the other end of the Lolo Trail until he caught up.[6]

With the fugitives approaching Montana, the Deer Lodge paper began its relentless criticism Howard. The Christian general had been outwitted by Joseph. “With a smaller force he has out-maneuvered Howard at every turn, and in a fair fight has been a match for his troop.” Joseph, lacking Howard’s “Sunday School training”, had coyly proposed surrender and then slipped away.[7]

Then came the Fort Fizzle Fiasco of July 28, 1877. As the hostiles approached the Bitterroot Valley on the Lolo Trail, the little band of soldiers under Captain Rawn, supplement ed by volunteers built a barricade across a narrow portion of the trail. Somehow, Joseph either negotiated his way through their lines or found a way around them. Though the situation was tense, there were no casualties on either side. The Nez Perce then entered Montana’s Bitterroot Valley. So far, they bore no grudges against the local populace. They would proceed southward trading peaceably with the settlers and committing no depredations. Joined by Rawn’s small force, Gibbon would follow them to the Big Hole.

Meanwhile General Howard was catching more hell in the press. The Benton Record called him “Granny” Howard. Others accused him of not being aggressive enough in his pursuit. Some said he often stopped too long to lick his wounds or to hold Sunday services. His failure to catch Joseph on the Lolo Trail drew heavy criticism. His defenders, like Deputy U.S. Marshal Robbins of Idaho, claimed that the Nez Perce would have ambushed him from the two barricades he insisted had been built across the trail. Howard boasted that he had decisively beaten the Indians at the Clearwater. Like his boss, McDowell, he saw driving the hostiles out of Idaho and into Montana as a great achievement. He went on to assert that he had never rested and had taken the offensive at all times. He complained about his men having to march to the limits of human endurance. He called the stories of his inefficiency and slowness “palpably false”.[8]

On August 9, Howard wrote a letter to Montana Governor Potts to justify his actions. His cavalry was a day ahead of his infantry. He was pushing rapidly ahead to join General Gibbon.

With the Nez Perce now in Montana, panic began to overtake the territory’s scattered population of settlers, miners and ranchers. Rumors persisted that other dissatisfied tribes, like the Blackfeet and the Crow might join up with the hostiles. The feared Lakota Chief, Sitting Bull was camped in the Cypress Hills of the nearby British possessions. Would the victor at the Little Big Horn come to the aid of the renegades?

Alerted by Howard, the troops under General Gibbon at Fort Shaw were pressed into action. Marching first to Missoula, he collected Captain Rawn’s company and some local volunteers for the pursuit of Joseph. Gibbon found the hostile camp at the Big Hole. On the morning of August the 9th, he attacked the sleeping Nez Perce. In spite of the surprise, the battle did not go well for Gibbon’s force. The Nez Perce quickly rallied. They killed about thirty of the attackers, captured and disabled their Howitzer and drove Gibbon off to lick his wounds. Late to the ball as usual, Howard came up in time to help bury the dead. Then he resumed his pursuit.[9]

On August 31, the Deer Lodge paper reported that Howard had reached Henry’s Lake on the evening of the 24th close behind the Nez Perce. Stephen Frum told the paper that the Nez Perce fires were still warm when Howard arrived. Rather than pursuing the hostiles, Howard set up camp. The next day he went to Virginia City to get supplies. That resupply effort would detain the troops for 3 very long days. Frum also alleged, “Howard’s whole command was disgusted with the way they are doing, and denounce him as being entirely unfit for the position he holds…. He not only does not try to overtake the Indians, but allows them to catch him napping; his men will desert him; he travels no further in a day when within striking distance of the hostiles than he did crossing the Lo Lo Trail.” A month later the paper reported Frum now maintained he had been misquoted. He said there had been no burning Nez Perce campfires and that he did not say that: “Howard’s whole force was disgusted with the way they were doing.”[10]

Probably the only paper in the Montana Territory defending Howard at this point was the Herald of Helena. After news of the disaster at the Big Hole reached them, the Herald insisted that Howard was probably “hurrying forward in pursuit of the savages.….We believe Howard will not tarry an hour in the chase.” The paper went on to cite Howard’s bravery in his encounters with Joseph in Idaho and his heroism in the Civil War battle at Fair Oaks where he lost his arm.[11]

As panic swept the Montana Territory in the wake of the Big Hole Battle, the Weekly Herald summed up the grim picture with headlines like:

Stage coaches stopped.

Telegraph wire torn down.

United States mails suspended.

Through travel altogether suspended.

Express and freight to railroad effectually corralled.[12]

As the hostiles passed through Horse Prairie, it was reported that they had attacked a train of freight wagons on the 20th of August. They killed five men and captured a large amount of ammunition intended for Salmon City. Then the Nez Perce headed for Yellowstone Park where they killed couple of tourists.[13]

On the night of August 19, Howard was close to catching up with the Nez Perce. He camped on Camas Creek, near modern Dubois, Idaho. That was a mistake. The hostiles had camped there the night before. At 4AM, a raiding party attacked Howard’s camp bent on capturing his horses and mules. They managed to take most of the mules and a band of horses belonging to the volunteers. Some of the demoralized volunteers simply went home in disgust and claimed top dollar for the loss of their mounts. Losing his pack animals further slowed Howard down. Thirty years later, Howard would claim (falsely) that he recovered most of the lost stock.

Following the Camas creek debacle, the Deer Lodge paper published a long article critical of General Howard. Howard had been slow to move to support Gibbon during the Big Hole Battle. When he got there, he wasted time burying Nez Perce dead. The paper speculated that Howard wasn’t up to the task of fighting the hostiles. He had allowed himself to be tricked by propositions of surrender by the Nez Perce at Cottonwood. Then he lost a major portion of his pack train at Camas Creek, reducing his mobility. The Nez Perce, “have achieved renown for intrepid courage and indominatable purpose….” The article then suggested Howard be replaced by a more competent commander.[14]

The New North West’s article was almost prophetic. On August 24, Howard began an exchange of communications with General of the Army, William Tecumseh Sherman. Sherman had made his way to the Montana Territory to monitor the unfolding events. Howard complained about the fatigue of his men and mounts after losing most of his pack animals at Camas Creek.

He begged Sherman, “What I wish is that by some eastern force the hostiles be headed off before they disaffect the Crows or unite with the Sioux….I hear that Miles, probably Sturgis, is on the Yellowstone, not far from my front.”

In response Sherman told Howard that his force should “pursue the Nez Perce to the death, lead where they may.” Then he struck a blow at Howard’s military prowess, “If you are tired give the command to some young, energetic officer, and let him follow them….”

A chastised Howard responded that, “You misunderstood me; I never flag.” It was his command, including its “most energetic young officers, that were worn out…. You cannot doubt my pluck and energy.”[15]

The New North-West continued to heap scorn upon Howard as the hostiles repeatedly outdistanced him. They quoted the Helena Herald as saying, Howard “fights his battles in the newspapers, and Gibbon hunts Indians and fights them.” Howard had been “outgeneraled” and “as an Indian fighter (he) is a dead failure.”[16]

The Nez Perce next sought help from the Crows of the Yellowstone country. The Crows, however, valued their relations with the Whites and refused to join or aid the hostiles. Many of them signed up to serve as scouts under Colonel Sturgis. Operating from the tongue river Cantonment, near the future Miles City, Sturgis had joined the chase. Sturgis and the Crow scouts caught up with the Nez Perce as they left the Yellowstone via the narrow confines of Canyon Creek, just west of modern Billings. The Crow managed to capture several hundred of the Nez Perce horses and even claimed to have taken a few scalps. The route up Canyon Creek took the Nez Perce north to the Musselshell which flowed into the Missouri. It was now becoming clearer that they intended to make a dash for the border and seek refuge with Sitting Bull’s Lakota.[17]

The Nez Perce crossed the Missouri River at Cow Island. The island was an important transfer depot for Missouri river traffic when the water was low. A trail led up Cow Creek to Fort Benton, where the goods could be distributed. The Nez Perce besieged the dozen soldiers guarding the supplies, pilfered what they could and set fire to the rest. Simultaneously, they attacked a train of freight wagons bound for Fort Benton, killing one man. They looted and burned the wagons as well.

By now Sturgis had turned back and encountered Howard to his rear. As they joined forces, it looked very much like the Nez Perce would soon escape to Canada. Howard wrote that, “There was little hope of overtaking the Indians by direct pursuit.” Howard then sent a dispatch to Colonel Miles at the Tongue River Cantonment near Miles City. “I earnestly request you to make every effort in your power to prevent the escape of this hostile band, and at least to hold them in check until I can overtake them.”

Miles answered in the affirmative, but cautioned, “I fear your information reaches me too late for me to intercept them, but I will do the best I can.” Some of Miles’ best troops were already serving under Sturgis’ command, but he resolved to make do with what he had. Earlier Miles had dispatched a party toward the Missouri yo protect supplies. He figured he could add them to his forces. To make his troops more mobile, he mounted his infantry on captured Indian ponies. He also requested a supply steamer to be dispatched from Fort Buford to support both his own and Howard’s forces. Leaving Tongue River on September the 18th. He had hoped to head off Joseph before the hostiles crossed the Missouri. But, by the time he reached that river couriers from Cow Island informed him of Joseph’s crossing. Miles’ only chance of catching Joseph was to outrace him to the Milk River country. He used his cannon to hail the steamer Fontenelle and crossed the Missouri. Then he marched around the east side of the Little Rockies. Sensing that Howard and Sturgis were lagging far behind, the Nez Perce stopped to rest at Snake Creek, just short of the Milk River, their last obstacle on the way to Canada. Later, the Helena Herald would proclaim that Howard’s strategy had been to take pressure off the Nez Perce by slowing his pursuit. This allowed Miles time to intercept them as they paused at Snake creek. (Source: Nez Perce NHP: Nez Perce Summer, 1877 (Chapter 11) (nps.gov) )

Meanwhile, Howard told his companions that he, “had asked the great Master for success, even if the credit were given to another.” His prayer was soon answered as a messenger reached his column with news that Miles had intercepted Joseph and had him besieged at Snake Creek near the Bear Paw Mountains. By the time he reached the Missouri, the steamer Benton was waiting to take him across. The battle had simmered down when Howard approached the lines of Colonel Miles. Wisely, he left Miles in charge and offered the use of his Nez Perce interpreters to help Miles arrange the surrender. The six-day battle ended with Joseph’s surrender on the following day, October the 5th, 1877.

Even after the surrender of the Nez Perce, some Montana papers continued to eviscerate General Howard. The Benton Record blamed the protracted chase on Howard’s “non-come uptiveness.” At first Howard had under-estimated the strength and military capabilities of the hostiles. The paper said that by the time he realized his mistake, his force was too “broken down to rectify the error.” Howard clearly felt the need to defend his reputation after the surrender. In a battlefield interview with a reporter from the Record, Howard complained “that all of the newspapers from Montana were liars.” [18]

In his 1907 book, Howard summed up his campaign against the Nez Perce, “In peace the non-treaty Nez Perces were restless and fretful, in war none fought with greater bravery, nor do I believe that any other body of Indians was ever more ably led than they under Chief Joseph, who displayed consummate generalship in his conduct of the campaign.”[19]

Perhaps the Nez Perce had a better description of Howard than he did of them. They called him “General-Day-After-Tomorrow”.[20]

LDT 13 Feb ‘20

[1] My Life and Experiences Among the Hostile Indians. 1907. O.O. Howard

[2] Ibid. Howard.

[3] The Avant Courier, Bozeman, Mont. Terr. June 28, 1877.

[4] The New North-West. Deer Lodge, Montana. June 22, 1877.

[5] The New North-West. Deer Lodge, Montana. July 13, 1877.

[6] The Avant Courier. July 26, 1877. Bozeman, Montana Territory.

[7] The New North-West. Deer Lodge, Montana. July 27, 1877.

[8] The Avant Courier. August 16, 1877. Bozeman, Montana.

[9] The New North West, Deer Lodge, Montana. August 17, 1877.

[10] The New North-West. Deer Lodge, Montana. August 31, and September 28,1877.

[11] Helena Weekly Herald. Helena, Montana. August 16, 1877.

[12] The Weekly Herald. Helena, Montana. August 23, 1877.

[13] The Helena Weekly Herald. Helena, Montana. August 30, 1877.

[14] The New North West. Deer lodge, Montana. August 24, 1877.

[15] The Weekly Herald. Helena, Montana. December 6, 1877.

[16] The New North-West. Deer Lodge, Mont. Sept. 7, 1877.

[17] Helena Weekly Herald. Helena, Montana. September 27, 1877.

[18] The Benton Record. Fort Benton, Montana. October 12, 1877.

[19] Ibid. Howard.