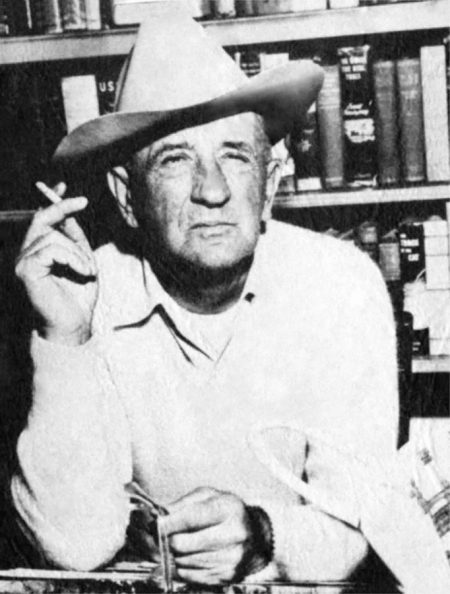

friend and ranching partner

Jim Thornhill in his later life in Arizona.

From: LOST PONY TRACKS

By Ross Santee, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln (1953)

CHAPTER IX

A CERTAIN cowman went into Charlie Collin’S. saddle shop in Globe to buy a saddle blanket, picked out the blanket he wanted and asked the price. “Isn’t that a little high?” the cowman asked.

Charlie pitched the blanket onto the highest shelf as he replied, “It’s a damn sight higher now.”

It was “take it or leave it” with Charlie, who still makes and sells the best. But I’d hesitate to say how many pieces he has made and given away to friends.

Most cowboys checked in at Charlie’s when they came in from the range. Cowboys looking for work left their gear at Charlie’s ; and there were always the old-timers who cluttered up his place, old-timers who had played their part and knew the West when it was young. And Charlie worked through all the talk, always with long ears. In talking about San Angelo, Texas, Charlie was queried as to what he knew about the town. “Not too much,” said Charlie, “but I used to drown out prairie dogs where the court house stands today.” If Charlie hears of a book or pamphlet about Texas or the Southwest that he doesn’t own he does something about that too. “I’m just a pack rat,” he says.

[165]

As for guns, Charlie owns more six-shooters, rifles and Carbines than Francisco Madero, Charlie Sweeny and their little crowd had available when they rode across the Rio Grande and started the Revolution. And they are not Just guns to Charlie; he knows the history back of each gun. If you happen to be interested and a particular friend Charlie will close the shop. “Now,” says Charlie, “we can talk without interruptions.”

While I hold a great admiration for Will James’ work, I have always agreed with Charlie that when it came to interpreting the cowboy—in bronze, drawing and painting—Charlie Russell stood alone. Charlie has most of Russell’s prints; he will name each gun in the picture, as with a saddle, and the year that they came out. When Charlie and certain old-timers bend a critical eye no detail is overlooked.

In the shop one day, looking at a certain print, I asked if the Indians might be Comanches, and a handsome, white-bearded man in his eighties spoke. “They’re not Comanches: most always they slit the tip of a pony’s ear. The Comanches were fine horsemen. I’ve got a blanket like that one, though. If you’ll come up to the cabin I’ll be proud for you to see it. I was wagon boss for General Carr at the time; I shot three times at that Injun before I knocked him off his horse.”

The old-timer was Bill Young’s father who with Bill, his son, was running the Graham cattle in Pleasant Valley when Tom, the last of the Grahams, was killed down at Tempe. bush-whacking affair. In most aspects, that was the period in Arizona known as the Graham-Tewksbury feud or the Pleasant Valley War. A controversial subject to this day, some say as many as thirty men were killed. When I questioned Bill about it he always shook his head. “The fire was out

[166]

when we come in, but there was still plenty of smoke. Fact is, we were told to leave, but we happened to like the country. What I heard come pretty straight, but remember it come second-hand; for the ones who knew the most always had the least to day.”

When Zane Grey’s novel, To the Last Man, supposedly based on the Pleasant Valley War, was filmed and the Picture was shown in Globe I sat with Bill. The place was packed that night; they came from “Dan even to Beersheba” and as far north as the Tonto Rim. Bill pointed out various old-timers. “There’s ol’ so-an-so; he knows, an’ he’s one who will know for certain if this picture is right or if the thing’s all wrong.” When the fight at the cabin was shown Bill began to snuff and cut his tobacco thin because of certain technical differences he held with the director.

At the cabin fight—that is history—the Graham faction had surrounded a Tewksbury place in the night. When two men walked out of the cabin at daybreak they were promptly shot down and killed. The fire was returned from the cabin. It was during the thick of the fight that the ranch hogs began eating on the bodies. That was when the woman walked from the cabin, shovel in hand, drove off the hogs and buried he bodies in shallow graves. When she walked from the cabin door the Graham faction withheld their fire, and not a shot was fired by either side until she had finished her ghastly chore. When the woman re-entered the cabin the firing began on both sides and it was more intense than ever.

In the picture we saw that night no hogs appeared on the scene. It seems the director had substituted buzzards as being less offensive. Nor would Bill be appeased, “ ‘,I wasn’t there that day—an’ there wasn’t no buzzards, either.

[ 167 ]

It was when the hogs started eatin’ the bodies that the woman come out with the shovel, that’s known to be a fact. But if that’s as close as this picture comes to the truth, I want no part of it.” As an after thought Bill added, “There was a saddle blanket on one grave the first time I rode that way.”

One piece that Charlie particularly prizes is Kid Curry’s shotgun. Kid’s real name was Harvey Logan. Old-timers remember him as a train robber of considerable note and as the killer of Pike Landusky. Kid is also remembered by the Pinkertons, for after Kid made his way to South America he was never apprehended.

Kid Curry’s shotgun was given Charlie by Jim Thornhill, a mutual friend. im had been Kid’s pardner in Montana and Jim had also worked with Charlie Russell. As for the affection Jim held for his outlaw pardner and Charlie Russell, the artist, it appeared to be a toss-up; Kid might have had the edge since Jim’s oldest boy was named Harvey Logan Thornhill although everyone, including his father, always called him “Man.”

Jim was a regular at Charlie’s place. Since Jim knew of my interest in Charlie Russell Jim told me much about his friend. In looking at a Russell print one day | said to Jim,“

If Russell threw a loop as he painted one he should have been tops as a roper.”

Jim was serious when he spoke, “No, Charlie wasn’t a good roper or a good bronc rider; didn’t seem to be particularly interested in acquiring either knack. Many’s the time when a steer broke out of the holdup I’ve seen Charlie set his pony, never make a move when he could have had a throw. I used to wonder why, but I know now Charlie was seein’ things we didn’t see, and later he painted them in pictures.

{168}

Furthermore, I wouldn’t tell this to just anyone, they’d think I was knockin’ Charlie, but I know you’ll understand.

“Let a boy get bucked off, an’ Charlie would make a Picture. Many times I‘ve seen Charlie pull the wrapper from a tomato can, take a piece of charcoal from the fire—an’ sure enough, there would be the boy up at the end of his bridle reins; an’ I swear you’d know the horse. We’d pass it around and have a laugh, then it would be thrown away. It never occurred to any of us that some day everything Charlie did would be valuable, at least it didn’t to me.

“After Charlie quit the range and married he lived in Great Falls, Montana. Aside from the fact he quit drinkin’ Charlie never changed.” Jim chuckled, “Nancy, his wife, saw to it that Charlie worked in the mornings. An’ it was just as well, for he might never have amounted to much—that is as far as money was concerned, if it hadn’t been for Nancy.

He was so easy-going, if he liked a man he’d give his shirt away. An’ if Charlie ever had an enemy in his life I never heard of it. But Charlie’s afternoons were his own. When he’d show up on the street it wouldn‘t be long until there was a group of men around him, with Charlie the center of things. He was the best storyteller I’ve ever known. When people saw Charlie on the street they just gravitated to him.” Jim chuckled again.

That chuckle of Jim’s was as much a part of him as his generous and sensitive mouth. Against a swarthy skin and small black mustache his strong, fine teeth showed white and clean as a dog’s. Above medium height and powerfully built, Jim was a stand-out in any group of men. On the quiet side, he spoke in a low, well-modulated voice. But it was Jim’s eyes that I’ll always remember best; they were brown and

[169]

friendly honest eyes that literally danced and sang. In any group you could feel Jim’s presence above every other man. That inner strength, the core of the man, was something that was felt.

If men gravitated to Charlie Russell, boys gravitated to Jim, When he appeared on the street in Globe there was usually a boy or two with him, often a group of them. Walt Coburn, the writer, once told me of his first meeting with Jim. Walt’s father, who owned the Circle C in Montana, had died when Walt was a boy.[1] One chore assigned to Walt by his half-brothers was to wrangle the pasture each morning.

It seems Walt’s half-brothers not only lived in separate houses at the ranch, but each kept his own stock of whiskey. Walt laughed when he told me the yarn. “I had strict orders to always lock the door when I wrangled in the morning, evidently my brothers didn’t trust each other if any whiskey was involved.

“One morning after I’d wrangled I walked into my brother Bill’s office. ‘You played hell!’ he said. ‘When you locked the door this morning you locked Kid Curry’s pardner in. He come in during the night and went to bed—had to break a window to let himself out of the house.” I heard a chuckle then an’ there sat Jim, the first time I ever saw him. I saw a lot of him later, though, for when my brothers crowded me too much I’d run away and go to Jim’s. I was always welcome too. I’d stay awhile, then go back to the ranch and give it another try. But it wouldn’t be too long until I was back at Jim’s again.

“I remember one horse he gave me. Jim had good horses, too. When I rode back to the ranch on him my brother Bill told me to take him back to Jim’s.” Walt laughed again.

[170}

“Jim straightened Bill out about the horse. It wasn’t considered healthy to ever crowd Jim Thornhill.”

I asked Walt why he had never written the real story of Jim and his pardner, Kid Curry, Butch Cassidy, Longabaugh and other men of the Wild Bunch who dragged such a long loop in the North, for Walt probably knows more about them than any man living today. And I liked Walt for what he said, “I gave it a lot of thought and finally gave it up for the real story, as it was, would hurt a lot of innocent people.”[2]

Born and raised on a ranch in Montana, Walt knows the cowboy as few men know the breed. Years ago when an editor sent for him Walt made his first trip to New York, and having heard of the Bowery all his life Walt wanted to see the place. With the editor riding herd on him, they went; Walt, in his boots and big hat, about as inconspicuous as a white elephant on the loose.

“Hello, cowboy,” said one of the bums; “I used to be a cowboy, meself.”

Since one never knows where one of the breed will turn up, Walt stopped and walked to the man. “Just where did you punch cows?” asked Walt.

“Joisey,” replied the stew-bum, “used to milk twenty head.”

As long as Jim lived Walt’s relation to him was much as Jim’s own sons. They are Man, Bill and Bob. I was’ at the Cross S when I first: came to know the boys. They talked so much of “Jimmer” I finally asked Shorty, the foreman, if there was another brother. Shorty laughed abd shook his head. “No, he;s their father; you’ll like him, too, an’ when you do meet up with him you’ll know you’ve met a man.

[171]

Dog-gondest family I ever knew ; always laughin’ an’ jokin’, never any words. It’s not often on a roundup you’ll see three brothers fill their plates an’ start visitin’ each other as if they just met up: When Jim, their Dad, is around he’s the center of the bunch.”

The outfit was working from the lower ranch the night that Jim rode in. “What did I tell you,” said Shorty as the boys rode to greet their father. “Laughin’ an’ jokin’; an’ like I said, he’s already the center of things.”

Jim had a code of his own. I knew his affection for his boys yet I have heard Jim say he would rather see any of his boys dead than ever take a backstep when they knew they were in the right.

Unlike so many of his kind, Jim held no racial prejudice. Black, white, yellow and red, they were all alike to Jim. Yet he believed that no race as a whole was worth the powder to blow it to hell. To Jim the human race as a whole was a failure. Only the individual counted, no matter his color or creed—and a friend could do no wrong. From what Jim said it was evident that his pardner, Kid Curry, had certain positive ideas peculiar to himself.

After one train robbery Kid came back to the ranch. “How’d you make out?” said Jim.

“We got the money, all right, but I wish we’d killed fifty men.”

“Don’t you figger you might have got one good one if you killed that many?”

“Not according to the law of averages,” Kid replied. “You could go as high as a hundred an’ still feel safe that you wouldn’t kill a good one.”

The killing of Pike Landusky by the Kid has been written

[172]

many times. Jim and I were sitting on the curb in front of the Lodge Saloon the day he told me of it. A cowboy had just been acquitted of killing a man on the street in Globe: just across the street in front of the court house friends were shaking the cowboy’s hand. Jim shook his head, “Even if you’re acquitted it’s no fun to be tried for murder. I was tried once, myself.

“One morning at the ranch Kid caught up a horse, one of the best in his string. Kid said he was going to town.

‘Wait till I ketch a horse,” I said, ‘an’ I’ll go in with you.’

“No,’ Kid said. ‘I’d rather ride alone today. I figger on some trouble for I’m a-goin’ to give Pike a chance to make the talk he did that day when I was handcuffed. I told him then I’d give him a chance to say it all again when I wasn’t wearin’ bracelets, an’ I figger now’s the time.”

Jim chuckled, “I says, ‘In that case, Kid, I’ll go along whether I’m wanted or not.’”

“I don’t know whether you’ve ever been to Landusky or not but it sets in kind of a bowl. There was at least a foot of snow on the ground. We tied our horses at the rack, went into the saloon. There was probably twenty people there, playing cards and at the bar. Kid didn’t waste any time, either. He walked right up to Pike. ‘You said quite a piece,’ Kid says, ‘the day they had me handcuffed. I told you then I’d give you a chance sometime to say it all again. Now, talk! Says Kid. “You cussed me out that day, let’s hear it all again.’” Jim chuckled again. “Pike didn’t want any part of the Kid. ‘I want no trouble with you,’ Pike says. He din’t either; you could see it on Pike’s face.

“’Go on an talk,’ Kid says. I want to hear it all again—the things you said, the way you cussed me out the day I

[173]

wore the handcuffs.’ But Pike wouldn’t talk. So Kid up an’ slaps his face, an’ still Pike wouldn’t go for his gun. He wanted no part of the Kid, who slapped his face again; finally knocked Pike down an’ worked Pike over good.

“There were some in the crowd who wanted me to stop It. But I said, ‘No—Kid had waited a long time for this an’ Kid could go as far as he liked.’ An’ like I said, Kid worked Pike over good, finally quit of his own accord. Pike finally got to his feet. Kid never did take Pike’s gun. Kid had turned away to set on one of the card tables. Pike saw his chance, at least he thought he did. But he never did get the gun clear of the holster for Kid dove in an’ tore it from Pike’s hands.

Shot Pike with his own gun; fact is, he shot Pike twice.[3] An’ a funny thing happened then.

“There was a one-legged feller in the saloon who threw his crutch away an’ bolted out the door. (This was probably Jake Harris, the proprietor of the Saloon.) If this feller’d had two legs I’d had to of shot him in the back. We couldn’t have anyone spread the word or loose outside or they’d of shot us off our horses before we got out of town.” Jim chuckled again. “At that I never would have caught this one-legged feller if he hadn’t fell down in the snow, for some of the jumps that feller took on that good leg was all of twenty feet. I helped him up. ‘It’s cold out here,’ I says, ‘you’d better come in where it’s warm.’ ‘I don’t want to be murdered,’ he says. But I helped him up. “There won’t be any more shootin’ here,’ I says, ‘unless some of this bunch starts it. We took their guns, told them to stay inside until we got out of town. We had no trouble riding out.

“Kid wasn’t a big man but anything anyone else could do Kid could do it a little better. Good rider, good roper, good all round cow hand. Kid was a good miner, too, good

[174]

carpenter; things like that I couldn’t do. Easy to be around, unless he was crowded. Kid wouldn’t take anything, an’ he wasn’t afraid of any man or anything that ever walked the earth; an’ he was loyal to a friend.” Jim chuckled, “Kid’s still alive, of course; we don’t dare write but I’ve had word of him.”

“The trial?” I said. “You said you were tried.”

“That’s right, there was a trial. I’m away ahead of ‘myself. I stayed out with Kid six months before he quit the country. When I’d try an’ get him to leave he’d shake his head, ‘No, I owe a few little debts, when I get them squared I’ll leave; if the law runs into me that’s their own hard luck, not mine.’

“When Kid finally decided to pull out I went in an’ asked for a trial, myself. Walt’s father, Mr. Coburn, went my bail, put up ten thousand dollars.[4] I didn’t go to jail. At the trial the judge instructed the jury that there was only two verdicts he’d hold for; I was either guilty or innocent, there was no in-between business at all. And yet the jury had no more than retired when they sent word for the judge to come in, so he brought the jury back and instructed them again.

“I was sitting with Mr. Coburn. He says, ‘How does it look to you, Jim?’ And I said it didn’t look too good since the jury didn’t appear to know what they were about. I had a, six-shooter in my shirt front an’ I told Mr. Coburn if the verdict is guilty for him to lay down on the floor as I intended to shoot my way out. He got kinda excited then.

“’No Jim,’ he says, ‘I’ll go to the governor. I’ll go broke on you.’

“’You done enough,’ I says, ‘an’ I won’t go to jail, not even for five minutes; an you’ll get back the money you up if I have to hold up a train.

[175]

“’It’s not the money, Mr. Coburn says; ‘they’ll kill you, Jim, before you get out of here. I’ll go to the governor; I’m with you all the way.’

‘My mind’s made up,’ I says; ‘they may kill me before I get out of here but I’ll take some more along.’ We didn’t talk any more, I sat an’ sweat it out. The jury wasn’t out very long, just long enough to take a vote, but it seemed an age to me. The verdict was, ‘Not guilty.’ Next thing I knew Mr. Coburn was shaking my hand and friends were all about me, poundin’ me on the back.”

The group in front of the court house was breaking up. The cowboy who had been acquitted was heading towards the Lodge Saloon, surrounded by his friends. Jim nodded towards the cowboy, ‘“‘He’s young, he’s still a boy; but he will never forget this day no matter how long he lives.”

In one of Charlie Siringo’s books,[5] Siringo—a Pinkerton and range detective—wrote at some length about Jim. I had been asked to review the book by the New York Herald Tribune. I liked the first part of the book where Siringo told of his working years as a cowboy. But I did not like the second part where he snooped as a range detective; made frends, then turned them in. I knew Jim would be interested as to what Siringo said about him. When I gave Jim the book I told him how I felt and that I did not intend to review it. It took Jim a few days to read it. When I met him on the street he had the book under his arm, carefully wrapped in a paper. As usual when we met up we sat on the curb and and talked.

There was only one thing Charlie got a little mixed up about; that was when the team ran away. I carried him in, All right, but he was unconscious and out of his head; he got things mixed up there, but the rest he told was the truth.

[176]

When he told about our first meeting in front of the Saloon, Charhie’s horse was pitching with him; the pony pitched pretty hard too. Charlie’s six-shooter flew out of the holster. I picked the gun up; when the horse quit pitching I handed it up to him. I don’t know why he made a point of saying I gave him the gun butt-first: when you hand any man a pistol you don’t shove the barrel at him.” Jim chuckled again,

“I knew who he was all the time when I took him out to the ranch, and I knew his reason for wanting to come: he figgered if Kid or any of the Wild Bunch were still in the country they’d finally show up at my place. Funny thing,

While he thought he was watchin’ me all the time it never did occur to him that I was glad to have him around where I could keep an eye on him. Because I knew where Kid and the boys were all the time.

“Now as for a detective or Snooper, I don’t hold for one either. But Charlie had a job to do; I come to like him, too.

You said you didn’t intend to review his book. Course, that’s up to you. But you did say you liked the first part of it, so why don’t you write it that way? You can say you don’t like snoopers either, you can still be honest about it; for Charlie’s an ol’ man now an’ I hear he’s not too well. It might help Charlie a little. Course, that’s up to you. But all my life I figgered it never hurt me any to give the other feller a break.”

So I wrote the review as Jim suggested, gave: him the piece to read and it pleased me that Jim liked it. “It should help Charlie,” he said, “I hold nuthin’ against him. Even if I did, like I said, it never hurts to give the other feller a break. Charlie’s an ‘ol man now an’ I hear that he’s not too well.”

[177}

Of Jim’s boys I came to know Bill best. On one work at the Cross S outfit he slept in the tepee with Shorty and me. AIl the boys had their father’s eyes. and Shorty often said of Bill, “Bet he’s a ringer for his Dad when Jim was still a kid.” Bill was never without a six-shooter, he carried it in the waistband of his pants, it was as much a part of him as that hearty laugh. Good cowboy, and never one to bother about small details. Bill rode through that work with a broken horn loop on his saddle; simply slung his rope over the saddle horn, packed his rope that way.

On one drive, and coming off a steep hillside, Bill’s loop uncoiled; got under the pony’s tail and touched the pony off. As the pony bucked off the steep hillside Bill’s hat went first, his six-shooter followed, high in the air. Bill and the saddle went next. The pony was still wearing his bridle, how-ever, when he was caught at the holdup.

That night in the tepee Shorty said, “Bill, I hope you don’t mention this, it might give the Cross S outfit a bad reputation as far as the ponies go. Ya know, yerself, there’s lots of cowboys who shy away from an outfit where all the ponies pitch.”

Bill laughed that hearty laugh, “Listen, Shorty, if it’s left for me to tell this thing no one will ever hear it.”

Of Jim’s boys, Bob married and quit the cows; evidently a locomotive-whistle meant more than the bawl of a critter on the range. Man was cruelly hurt in as simple an operation as roping a little calf; unconscious for two weeks, he finally woke, with “Jimmer” at his side, but the hurt’s there to this day.

I’d been away from Arizona a long time. On my return I learned that my friend Jim was ill and in the County Hospital.

[178]

I found him coming from the toilet along a semi-darkened hall; his footing was none too steady as he groped along the wall. “It’s Ross,” I said.

He took my hand and gave his hearty chuckle. “Come,” he said, “come an’ sit an’ tell me all about him.”

“It’s Ross,” I said.

“I know,” he said. ““Now come an’ sit an’ tell me all about him. Somehow, I don’t remember things the way I should. I think I’m kinda crazy.”

When we came out of the half-light and into the lighted room I thought Jim would remember, but when I looked in my friend’s face I understood. Jim’s fine brown eyes no longer danced an’ sang, the light had gone from them. “Now, sit,” he said, “an’ tell me about Ross.” He chuckled, “I was at the Cross S the day that big calf kicked a bucket of black oil all over him. He used to ask me about Charlie Russell who was also a friend of mine. Ross made a drawing on a letter for me, too, like Charlie Russell did. Now tell me, how’s Ross makin’ out? I want to hear about him; no matter where he’s at I’ll bet he’s drawing pictures.”

Another old-timer came into the room; Jim introduced me as a man who had brought him word of Ross. It was hard to take; I finally excused myself. We shook hands; Jim walked with me to the door. “It was nice of you to come,” he said, “an? tell me about my friend.”

I never saw him again for only a short time later Jim started on his last long ride, the one-way ride that a cowboy rides alone.[6] “Don’t feel too bad,” Bill said. “While Jimmer always remembered me there were times near the end when he didn’t know Man or Bob. So don’t feel too bad about it, for he thought a lot of you. Ya kn

[1] This is an error. Walt Coburn’s dad, Robert, died in 1918. Walt, born in 1889, was an adult by then. Walt had a different mother than his older siblings. Their mother died in 1885.

- [2] Walt Coburn would later write that it was he as a boy of 11 held the relay ponies that enabled the escape of the Curry Gang. See Pioneer Cattleman in Montana: Story of the Circle C Ranch (1968) SEE ENDNOTE

[3] Note: Thornhill must have been stringing Santee along with this statement. All other sources say that Pike was killed with Curry’s gun which was tossed to him by Jim.

[4] Seems a bit high. That’s $350K in 2023 dollars.

[5] Santee is probably speaking about Siringo’s 1912 book, A Cowboy Detective. The book details Siringo’s undercover work in the Little Rockies where he befriended Jim Thornhill in 1900.

[6] Thornhill died on November 7, 1936. He is buried in Globe, Arizona.

Endnote: Here’s a summary of what Walt Coburn wrote about his involvement in the escape of the Curry Gang after the Great Northern robbery:

“It was July 3, 1901, and all that teenage Walt wanted to do was to go to Malta, Montana, and prepare for the Fourth of July rodeo. Instead his brother, Bob, gave him the ridiculous job that day of taking some horses up to the top of a butte and sitting there all day, then bringing them back in the evening if nothing happened.

Well something happened all right. In the middle of the afternoon Walt saw riders hurrying to him from way out on the prairie. When those riders got to Walt, they changed to the fresh horses and left Walt with the old horses before hurrying away. Walt recognized Kid Curry as one of the riders and knew they must have done something for which they needed fresh mounts immediately.

Walt took the tired mounts back to the home ranch. Bob got the cook to make Walt a steak and instructed Walt to stay with him in the ranch house. Not long later a sheriff and posse from Glasgow knocked on the door stating they were chasing Kid Curry and his gang who had just robbed the Great Northern Mail train at Wagner. The sheriff asked for fresh mounts and dinner. Bob Coburn said there would be no fresh horses, but his ranch cook would cook the men dinner for a dollar a man. Outrageous, but the sheriff said yes, so Bob sent Walt out to the cook house to wake up the cook and help in preparing the dinners. While preparing the dinners the cook said to Walt that he, too, thought the world of Kid Curry and that maybe they should slow that posse down. So they put something in the food that gave the posse diarrhea about five miles down the trail at Bear Gulch. Needless to say the posse never did catch Kid Curry and his gang.

-Reprinted from an article on the Circle C Ranch from the Montana Cowboy Hall of Fame.