A Montana Cold Case

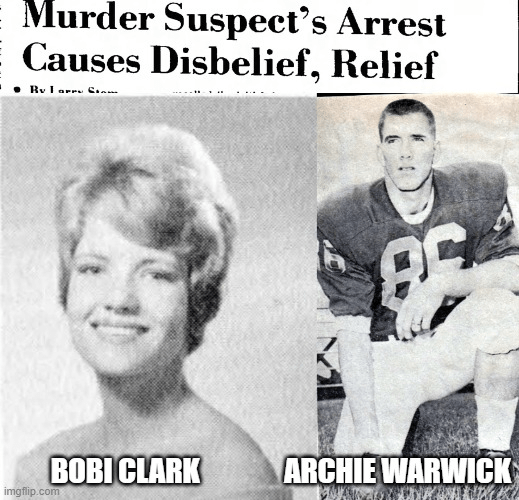

At 8:30 a.m. on December 23, 1964, Earl Plum, was driving along Cottonwood Road, south of Bozeman, Montana when he came upon the scantily clad body of a young woman.[1] The body turned out to be Roberta “Bobi” Clark. She was a first-year school teacher from Kalispell. Bobi had recently graduated from Montana State College (now MSU) at Bozeman, where she had been a cheerleader and Homecoming Queen candidate. The subsequent investigation would establish that she had been murdered.

Five years later, a man named Oliver “Archie” Warwick would be tried and convicted of the killing. In 1972, Warwick appealed his case to the Montana Supreme Court. His conviction was overturned. In its ruling, the court cited that a written statement documenting an interview of the defendant by a former FBI agent and private investigator named Burleigh Allen on Feb. 2, 1965 was not admissible. The court said the statement should not have been admitted because the original tape had disappeared and its accuracy could not be verified.[2] At his second trial in 1973, Warwick was found not guilty.

In December 1964, Bobbi Clark was a 21 year-old French Teacher at Flathead County High School in Kalispell. She was engaged to be married to Jack Wandler, a student at MSC in Bozeman. They had planned a Spring wedding. She was last seen arriving in Bozeman after midnight on December 23rd. Her locked car was found behind Wandler’s apartment. Footprints in the snow appeared to show her walking from the car toward the alley. A search was initiated by her fiancé when he woke up the next morning. Sadly, Earl Plum would find the body on Cottonwood Road about the same time the search began.[3]

The victim was found in her underwear, but her clothes were nearby. She was badly battered and bruised with broken bones. It appeared that she had been dragged across a bridge underneath a car. Her mother came from Billings later that day to identify the body. In a few weeks, the victim’s family would hire Burleigh Allen to help law enforcement with the investigation. Allen was a retired FBI agent. A fund was established to pay his expenses.[4]

As the investigation continued, it soon became evident that there wasn’t much physical evidence at the scene of the crime. One exception was a set of tire tracks possibly belonging to the car that had run over the victim. A plaster cast was made of the tire marks and sent to the FBI for evaluation. At first, the FBI could only say that the tires were similar to the Cordovan low-profile jet tire. Not satisfied with the FBI’s report, Bozeman Police initiated their own search of comparable tires at local tire stores. They found their match at the Bozeman Gambles store. The tire marks were made by Crest Imperial tires sold exclusively by the Gambles chain. The Gallatin County Sheriff began asking for any information about the tires in local media in early January 1965. Coincidentally, on January 15, a Bozeman resident reported that two tires had been stolen from his home. The person reporting the theft was Archie Warwick.[5] That afternoon, a Crest Imperial narrow white sidewall tire was found near Bozeman on Bridger Canyon Road by a citizen who took it to authorities. Three days later, a second Crest tire was found.

The FBI would now determine that the tires were of the same size, tread design and had the same degree of wear as those that had left the tracks at the crime scene. Attention turned to the tires stolen from Warwick. Investigation revealed that the tires were identical to those that had once been on a 1959 Chevrolet gifted to Warwick by his wife’s parents. The car’s previous owner had bought the tires before selling the vehicle to a Havre, Montana dealership.[6]

Law enforcement and investigator Allen then got Warwick’s permission to search his car and apartment for evidence. They put the vehicle on the rack at a local service station. Allen was struck by the fact that the car was very clean, even including the undercarriage. This would be unusual for a Montana car in the Winter season.[7]

Working with several law enforcement officers, investigator Allen then took a taped statement from Warwick on Feb 2, 1965. Allen would infer some self-incriminating evidence came from this statement. A 38-page transcript was made from the recording. At some point, the original tape was lost.[8]

Based on the scanty evidence available at the time, a Grand Jury in Bozeman issued no indictments in the Bobi Clark case.[9] On Saturday, March 13, Bobi’s purse was found by two highway workers just outside of Bozeman. Though it was sent to the FBI, no new leads were developed.[10] With no new evidence and a lack of witnesses, the case was growing cold.

Five years after the death of Roberta Clark, there was a break in the case. Headlines across Montana screamed, “Ex-MSU Gridster Charged in Clark Murder”. The accused was Orville “Archie” Warwick. Then living in Seattle, Warwick voluntarily returned to Bozeman to face charges. Bail was set at $30,000[11] There was a mixture of shock and relief across the state. Bobbi Clark had been a beloved teacher in Kalispell and Warwick was a sports legend at Havre High and MSC. New informants had obviously come forward in the case.

I was living in Warwick’s home town, Havre, Montana, at the time of his arrest. The case caught my interest. Though we had attended the same high school, I did not know Warwick. I had heard plenty about him, however. He had been a star athlete at Havre High. Before I transferred to Havre myself, I had heard his athletic prowess extolled as his team, the Blue Ponies, stomped all over my school, the Glasgow Scotties. Warwick left college in 1965 and returned to Havre. He played basketball in the Men’s City League for recreation.[12] While I was home on leave from the Marines in August 1965, my brother told me that Archie was an occasional drinking buddy of his. Some of my friends had a lesser opinion of Warwick. One warned me in the late ‘60’s that Warwick was back in town and looking for trouble. That night, I saw him hanging his entire torso out of a car window bellowing, “You want me?” I resolved to stay clear. Another friend of mine had to suddenly leave town when Warwick showed up to confront him about some beef between the two. When Warwick was arrested in late 1969, my friends tended to believe he was guilty. After Warwick was released on bail in early 1970, I noticed a flyer for an evangelical meeting where the keynote speaker was none other than Archie Warwick. It seemed to me that he was disingenuously trying to build a false narrative to mask his troublesome character. I made the mistake of expressing my opinion on Warwick’s guilt to a girl I knew at college. It turned out she was his cousin. She was not amused. Some opinions are better left unsaid.

After his arrest, Warwick’s mother-in-law posted his $30,000 bail.[13] Attorney Charles F. Moses of Billings, was hired to represent him. A motion by Moses to dismiss the charges was rejected by Judge W.W. Lessley.[14] Out of jail, Warwick returned to Havre where he played basketball in the Men’s City League again.[15] On April 12, Warwick’s mother, Helen, was tragically killed in an auto accident near Big Sandy, Montana.[16] Warwick’s murder trial convened in Bozeman on June 3, 1970.[17]

Witness testimony was fairly routine until the 4th day of the trial. It then took a bizarre turn toward the occult. The victim’s former fiancé, Jack Wandler, was questioned by defense attorney Moses about an incident with a Ouija Board that took place a few weeks before the murder. Wandler said that Bobi and a group of friends were playing with the board. Wandler asked the board if he and Miss Clark would ever be married. The device, according to Wandler, revealed that they would not be married because she would be killed.[18] Later in the trial a University professor was called to debunk the reliability of Ouija Boards. He testified that the devices were consciously or unconsciously manipulated by users to reach their conclusions. He stated that, “Whoever held the indicator had an unconscious wish for the death of this girl.”[19] His testimony introduced some speculation that Wandler, not Warwick, might have been the killer.

The second week of the trial focused on the tire evidence. The prosecution hammered on the fact that the tires appeared to have come from the ’59 Chevy owned by Warwick. They effectively tied the tires to their original purchase in Rudyard, Montana by the car’s previous owner. A witness from the Montana Highway Patrol explained that the tire tracks belonged to a vehicle that was 60 inches wide with a wheelbase of 118 inches plus.[20]

On Wednesday, June 18, the prosecution would call two bombshell witnesses. One was a former co-worker of Archie’s from the Buttreys Store in Bozeman. The other was a former friend and drinking buddy of the accused. Neither had been interviewed by authorities in the initial investigation.[21] In addition, the prosecution would call private investigator and former FBI agent Burleigh Allen to the stand. Allen would say that Warwick had admitted to knowing the victim and further stated that he had spent most of the night of December 22 drinking at a bar called the Scoop. He said he went home about 11:30PM. Since his wife and children were away, there was no one to verify his story. The testimony from the other two witnesses would be much more damning.[22]

First up was the co-worker, Judith Veltkamp. She was the wi8fe of a Bozeman Police Sergeant. She reported on a conversation she had had with Warwick, who worked with her as a box boy at Buttreys. They had spoken about noon on the day that the body was found. The prosecutor asked her about what Warwick had said to her at that time.

“A- He had come in from taking out an order of groceries and he said, ‘They have just found a girl that has been drugged to death. ‘

“Q- What did you say?

“A- I said ‘drugged?’ and he said ‘No, dragged.’

“Q- What did you say to that?

“A- I said, ‘Where was it?’ and he said, On a county road.’

“Q- And what did you say?

“A- I asked him who it was.

“Q- What did he say to that?

“A- He said that it was Bobbi Clark, and I asked him if he knew her and he said yes.’

“Q- While the Defendant was relating this to you, did he speak clearly?

“A- No.

“Q. Do you recall how he spoke?

“A- He, he was extremely nervous and excited.

“Q- Did he stutter at all?

“A-Yes, he acted like his tongue was too big for his mouth. He couldn’t get the words out.

“Q- Did the Defendant relate anything else to you during this conversation?

“A- I asked him how he found out about this and he said, ‘I heard it on the car radio when I took the lady’s groceries out.’”[23]

Under cross-examination Mrs. Veltkamp said she had told her lawman husband about the conversation at the time. She did not tell anyone else until she made her official statement on January 7, 1970.[24]

Next up for the defense was Warwick’s old friend, Dick Kount (or Kountz). Kount testified that he and Warwick had been drinking late one night in February of 1965. They decided to fetch their rifles and poach a deer using a spot light. They soon managed to shoot one. While dressing the animal, Warwick told Kount that he was the one who had killed Bobi Clark. Kount did not report this conversation to authorities until January 3, 1970. [25]

The defense then called witnesses to shift blame from Warwick. The owner and an employee from the service station where Warwick’s car had been inspected in 1965 said they saw no damage to the undercarriage. This might have thrown some doubt on the prosecution’s assertion that Bobi Clark had been drug under Warwick’s car. (One might note that a 1959 Chevrolet had a full frame underneath it that would likely not show much damage from dragging a human body.) Their star witness was another former MSC football player, Robert Stephan. “Warwick, looking relaxed in a green suit, chatted …. with Stephan at one point in the proceeding”. On the stand, Stephan admitted to having told two women that he had killed Bobi. Apparently, this was just some idle boast as he had an alibi and was never seriously considered as a suspect. Another defense witness said he saw a motorcycle rider going up Bridger Canyon with two automobile tires on Christmas Eve 1964. As the defense wrapped up its case for the day, Warwick was feeling confident. Someone asked him how he slept. His response was, “Like a baby!”[26]

After a two-week trial, the case went to the four-man, eight-woman jury on June 22, 1970. The next day, the jury came back with its verdict: Guilty! Surprisingly, Warwick was released on his $30,000 bond while awaiting sentencing.[27]

Warwick returned to court on July to learn his fate. The headlines would read. “Warwick Given Life Sentence”. The Daily Interlake would report that Warwick, who seemed visibly shaken when he was found guilty, now showed no signs of emotion when the sentence was passed. The only visible sign was a wink and a smile from his wife as he was led from the courtroom.[28] His attorney, Charles Moses, would immediately appeal the case on multiple grounds.

The Montana Supreme Court would overturn Warwick’s conviction and grant him a new trial on February 24, 1972. Admitting the transcript of the interview of Archie Warwick conducted by Burleigh Allen in 1965 had been the fatal flaw in the original trial. With the original tape lost, there was no way to verify its accuracy.[29]

Warwick’s new trial was originally set for May of 1972. His attorney, Charles Moses, filed a motion to disqualify the original judge, W.W. Lessley, from presiding over the second trial. Under Montana law, the request was automatically granted.[30] This seemed only logical because of the judge’s admission of the disputed statement that got the case to be retried. Judge Jack D. Shanstrom of Livingston was named to hear the case. Moses had filed two other motions on Warwick’s behalf. One was to have him released on bail while awaiting trial. This was denied by Judge Shanstrom in August. Moses had also asked for a change of venue claiming Warwick could not get a fair trial in Gallatin County.[31] Moses then appealed the bail denial to the state’s high court.[32] By September, the court would grant bail citing that “Warwick is not a security risk” and that his conduct in prison had been good. The court also noted that he had been granted bail both before and after his original trial. [33] After attempting to find an impartial jury in Bozeman, Judge Shanstrom finally granted the defense motion to move the trial to another location.[34] The trial was moved to Great Falls, where testimony would begin on January 9, 1973.[35]

In the new trial, the tires alleged to have been on Warwick’s ’59 Chevy would continue to be the most compelling evidence. Defense attorney Moses would argue that the tires had been stolen from Warwick and that the tracks didn’t match the wheelbase of his car. Lieutenant Cutting of the Bozeman Police Force would testify that “the tire tracks showed an overlap, with the track of the front tires showing at the edges of the marks left by the rear tires.[36] (See note below on ’59 Chevy specs.)[37]

Warwick’s attorney asked Sheriff Anderson about physical evidence that was now missing seven years after the murder. Bozeman officers had sent fingernail scrapings, hair and textile fibers, blood, soil and grease to the FBI for analysis in 1965.[38] Also still missing were the original tapes made by authorities while interviewing Archie Warwick in early 1965. Without the tapes, the written transcripts were no longer admissible. In spite of the Supreme Court ruling, investigator Burleigh Allen and Oleta Davis from the Gallatin County Attorney’s Office both swore the transcripts were accurate.[39] A guard from the state prison testified that Warwick had told him, “They say I killed a girl. I don’t remember if I did or didn’t. I don’t know.” Testimony by Dick Kountz wrapped up the case for the defense. He retold the story of Warwick’s late-night confession while dressing out a poached deer in 1965. Asked how he felt about the revelation, Kountz said, “It bothered me for a second, but another vehicle came down the road and spooked us off.” Asked why he didn’t go to law enforcement earlier, Kountz stated, “I didn’t go to them, the law enforcement people came to me.” Then he added, “I didn’t think much of it anymore.”[40]

Finally, it was time for defense witnesses. Some were called to verify that it was common knowledge in Bozeman by noon on December 23, 1964 that a woman’s body had been found outside of town. This weakened the testimony given by the Buttreys co-worker on Warwick knowing about the murder before anyone else. Though Charles Moses didn’t have much to refute the compelling tire evidence, he called Warwick’s Father-in-Law to the stand. He testified that his daughter had called him “before suppertime on January 15, 1965 to say that two tires had been stolen from Warwick’s back porch.” The mother-in-law gave a slightly different version of the story claiming it was later in the evening and that she had taken the call.[41]

Then the arguments were over. Orville Archie Warwick’s fate was in the hands of the five-woman and seven-man jury. The Daily Interlake, Bobi Clark’s hometown newspaper, had expended a lot of ink over the last seven years on the case. It’s small headline on January 21st was anti-climactic. It simply read, “Jury Frees Warwick” . Some Montanans were ecstatic. Others, not so much.

In the courtroom, Archie “jubilantly clutched his wife, his attorneys and his wife’s parents.” Then he said, “I just say praise God, that’s all I can say. It’s been in His hands since the beginning. A lot of people have been praying and supporting us, especially groups from the prison-especially I want to mention the prison.”[42]

Archie was now a free man. Would he go back to his old days of drinking, carousing and fighting? Maybe not. To celebrate his freedom, he returned to his pre-trial evangelism. He was scheduled to speak at a July 8 rally in Helena that featured born again writer/evangelist Nicky Cruz. When the author of “The Cross and the Switchblade” cancelled, Warwick would become the headline speaker.[43] It was not a fluke. Archie would spend the rest of his life following the Lord and inspiring others.

After spending five years of mission training & work with Youth With A Mission in Kailua Kona, Hawaii, Archie would relocate to Lubbock, Texas. He would finally earn his BA in education at Lubbock Christian University. Then he would spend thirty years as a beloved teacher and coach at Trinity Christian Schools. He died on April 23rd, 2016.[44] Archie Warwick Memorial Stadium at Trinity Christian was named in his honor.

Roberta “Bobi” Clark is said to be buried in Billings, Montana. Shortly after Warwick’s acquittal, her sister asked the Bozeman Lions Club to give the reward fund collected for her killer to be used to help the family of a seven-year-old Michigan girl who had gone missing in Montana.[45] The 1965 MSC college annual, The Montanan, dedicated a page in memory of Bobi.[46]

LDT Apr 11, ‘21

Main Menu: http://www.azrockdodger.com

[1] No. 11988 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF MONTANA 1972. untitled (justia.com)

[2] Ibid. No. 11988

[3] The daily Interlake. Kalispell, Montana. 24 Dec 1964.

[4] The daily Interlake. Kalispell, Montana. 22 Jan 1965.

[5] Ibid. No. 11988

[6] The Daily Interlake. Kalispell, Montana. Jun 12, 1970.

[7] Ibid. No. 11988

[8] Ibid. No. 11988

[9] The Daily Interlake. Kalispell, Montana. Feb 10, 1965.

[10] The daily Interlake. Kalispell, Montana. March 14, 1965.

[11] The Daily Interlake. Kalispell, Montana. 31 Dec. 1969.

[12] The Havre Daily News. Havre, Montana. Jan 11, 1966.

[13] The Daily Interlake. Kalispell, Montana. Jan 20, 1970.

[14] The Daily Interlake. Kalispell, Montana. Mar. 2, 1970.

[15] The Havre Daily News. Havre, Montana. Feb 17, 1970.

[16] The Daily Interlake. Kalispell, Montana. Apr 13, 1970.

[17] The Havre Daily News. Havre, Montana. June 4, 1970.

[18] The Daily Interlake. Kalispell, Montana. Jun 11, 1970.

[19] The daily Interlake. Kalispell, Montana. Jun 21, 1970.

[20] The Daily Interlake. Kalispell, Montana Jun 17, 1970.

[21] The Daily Interlake. Kalispell, Montana. Jun 18, 1970.

[22] The Daily Interlake. Kalispell, Montana. Jun 18, 1970.

[24] The Daily Interlake. Kalispell, Montana. Jun 18, 1970.

[25] The Daily Interlake. Kalispell, Montana. Jun 18, 1970.

[26] The Daily Interlake. Kalispell, Montana. Jun 19, 1970.

[27] The Havre Daily News. Havre, Montana. Jun 24, 1970.

[28] The Daily Interlake. Kalispell, Montana. Jul 13, 1970.

[29] Ibid. No. 11988

[30] The Daily Interlake. Kalispell, Montana. May 2, 1972.

[31] The Daily Interlake. Kalispell, Montana. Aug 9, 1972.

[32] The Daily Interlake. Kalispell, Montana. Aug 21, 1972.

[33] The Daily Interlake. Kalispell, Montana. Sep 1, 1972.

[34] The Daily Interlake. Kalispell, Montana. Nov 15, 1972.

[35] The Havre Daily News. Havre, Montana. Jan 9, 1973.

[36] The Havre Daily News. Havre, Montana. Jan 12, 1973.

[37] The 1959 Chevrolet had a tire track width of 60.3 inches front and 59.3 inches rear and a wheelbase of 119 inches. This corresponds closely with the testimony in the first trial that the car that ran over the victim had a track width of 60 inches and a wheelbase of 118 inches plus. In a straight line, the rear tires would overlap the inside edges of the fronts by ½ inch on each side.

[38] The Daily Interlake. Kalispell, Montana. Jan 16, 1973.

[39] The Daily Interlake. Kalispell, Montana. Jan 17, 1973.

[40] The Havre Daily News. Havre, Montana. Jan 18, 1973.

[41] The Havre Daily News. Havre, Montana. Jan 18, 1973.

[42] The Daily Interlake. Kalispell, Montana. Jan 21, 1973.

[43] The Daily Interlake. Kalispell, Montana. Jun 29, 1973.

[44] Obituary at Archie Warwick Obituary – Lubbock, TX (dignitymemorial.com)

[45] The daily Interlake. Kalispell, Montana. Aug 28, 1973.